Kemi Lawson spent the first part of her career working in the City, before she decided to shift lanes. She recently launched The Cornrow, an online homeware and lifestyle store tailored to a modern Black aesthetic. Through her Instagram channel, she is also focused on educating her followers on the widely overlooked history of Black interior design.

Moving house with a husband and two young daughters inspired a quandary familiar to many – how to transform a property into a loving family home that reflects who we are. Our new abode in North West London was a 250-year-old listed cottage, so we decided to use the interiors to celebrate our history and heritage as a Black British family of both Nigerian and Jamaican descent.

I started researching interior design with a focus on what I loosely termed the modern Black aesthetic. I began with interior design magazines, especially those tailored to period homes and country cottages, and supplemented them with coffee table books, Pinterest and Instagram. Simply put, I have never felt more unseen as a Black British women than in the pages of interior magazines. Did Black people not buy homes? Did we not design interior products? Were there no interior styles or trends that could be attributed to Black culture? Evidently not, according to the piles of interior titles which now filled my home. The coffee table books were not much better; a huge tome called A History of Interior Design, purporting to tell the story of 6,000 years of global interiors, devoted a laughable two pages to the Black experience, and these both on Ancient Egypt. Others I found on Black interiors were often out of print and out of date.

Undeterred, I turned to social media. I set up an Instagram account, @cottagenoir, and dived in to share my stories and to learn from others. But here dominant voices belonged to white middle class women, and the dominant aesthetics, scandi, hygge, boho, cottagecore, simply were not the stories I wanted to tell. I felt increasingly frustrated, upset and lonely.

And then on 25 May, George Floyd was murdered, and everything changed.

Amid the global outcry, there was a sudden realisation of all the different facets of life where Black voices have been stifled, including the interiors world. The industry realised that Black homes matter. In fact, I believe Black homes really matter; they are an expression of Black joy and the Black everyday experience – an important counterpoint to the pervasive imagery and discussion of Black trauma. The interiors pages started to proactively look for Black content, and even I found myself on the pages of a few magazines. I started curating the missing stories on the history of Black interior design through my Instagram account. I worried that without understanding the history, Black design would continue to languish in the clichéd realms of animal print, safari chic and brash wax prints from Holland (more of the latter later). It would continue to be categorised as ‘tribal’ or ‘ethnic’. I love elements of all of these styles, but I knew, as author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warned, of the danger of a single story. We were and are so much more than this.

As my research intensified and I unearthed more on the history of Black interior design, I started sharing these stories via Instagram. The response was overwhelming. I discovered the breadth of Black interior design and the extent to which Black culture has contributed to the industry, and the way we decorate our homes. Below are just five hallmarks of Black interior design that have influenced how we live today.

Bold maximalism

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

In so many of the spaces that I researched, there was no time for minimalism, the conventional requirements of restraint, or the limitations of what is widely considered to be ‘good taste’. Instead, I saw a joyous celebration of colour and the thrill of displaying the material possessions that we had worked so hard for and purchased. The best reference here is the history and tradition surrounding the West Indian Front Room. This is a specific aesthetic to the Windrush generation, where West Indian immigrants would reserve a special room in their homes for best and use it to display art, possessions and family photographs within the sweep of a headily decorated room filled with swirls of carpet and curtain. This quintessential aesthetic is to be permanently celebrated in a new exhibit in the UK’s Museum of the Home (formerly the Geffrye Museum, recently renamed as an acknowledgment that Robert Geffrye was a slave trader, I know, you couldn’t make it up).

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

In my home, an understanding of this aesthetic has led me to be extremely confident with colour and pattern. The question is never ‘does it go?’, but rather, ‘do I love it?’, because I notice that, if I love it, then it always seems to go!

The beauty of textiles

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Any examination of the history of Black design will put the art of textile-making firmly in the foreground. Over and over again, I discovered beautiful and intrinsic textiles, used not only to clothe but also to tell powerful, moving stories. Asafo flags from Ghana illustrate meaningful proverbs, Adinkra textiles convey meanings of life through the use of 53 different symbols. There is the 500-year-old textile tradition of the Adire indigo fabrics of Nigeria, and the monumental quilts sewed by enslaved women in North America. There are also a growing number of contemporary Black owned textile houses with fresh perspectives, including high-end Haitian design house Yael et Valerie and the African American designer Sheila Bridges, known on Instagram as the Harlem Toile Girl.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Something all these textiles have in common is that they are not the brightly coloured Dutch wax prints now synonymous with African design. These fabrics originated in, and are designed and manufactured in Holland from the 1840s up to now (with a few China imitations). In 1846, Dutch entrepreneur Pieter Fentener Van Vlissingen realised that he could mechanise the method used on prints on batiks, a cloth popular in Indonesia. His company Vlisco introduced the fabrics to the Gold Coast, where it became popular in West African markets quickly.

The irony of a fabric from Holland widely mistakenly considered African design isn’t lost on me, neither is the sadness that these imported fabrics displace the traditional artisanal skills which are in danger of dying out. In my home, I proudly display indigenous Black textiles and love how they create a special warmth to my home.

Intricate woodwork

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

We all rightfully revere names such as cabinet-maker Thomas Chippendale and potter Josiah Wedgwood. But why do we know so little about master carpenter Henry Boyd, genius potter David Drake or countless other Black craftspeople working across the same period of history? Even in the present day, the name Khadambi Asalache may not ring a bell, but his home at 575 Wandsworth Road, is a National Trust property. The late civil servant had carved intricate panels throughout his entire home which are so devastating in their beauty that they are now rightly protected for us all to enjoy.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Visual tributes to family heritage

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

A reverence for ancestors and heroes of the past is a key feature of many Black homes both historically and today. Black living rooms often feature obligatory pictures of Martin Luther King and Malcom X, situated next to blonde-haired blue-eyed Jesus. There is also a love of black and white studio portraiture of family members, and a near universal fondness of enlarged graduation pictures. The seminal portraits by Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe in the 1960s are wonderful examples of this art.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

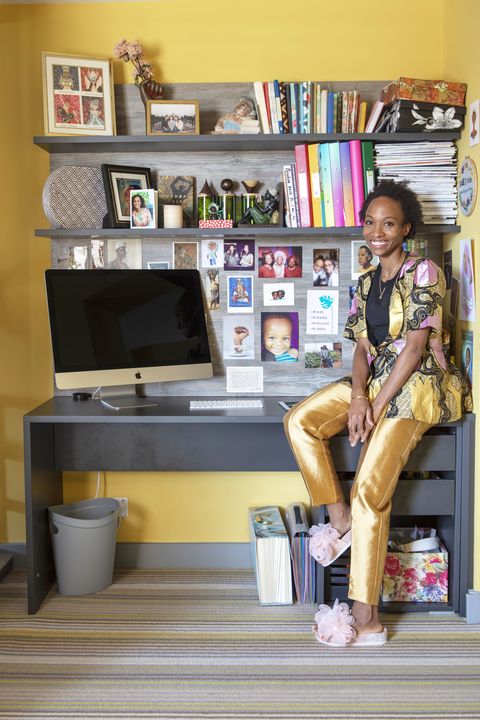

The white British upper classes also still celebrate their ancestors through imposing portraits of illustrious forebears. For the most part though, this reverence of our heritage has fallen out of favour. In my home, I have an ancestor wall where I have curated photographs of relatives, going as far back as possible, with a few Black heroes thrown in for good measure. My question is, why doesn’t everyone have an ancestor wall?

A love of earthy tones

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

There is a widespread notion that Black homes are full of vibrant colour, and while this is true for many, earthy shades are also very popular. The original African colour palette was often characterised by more subtle colour tones – earthier hues derived from the traditional African vegetable and plant based dyes, which were found in leaves, bark, soil and flowers.

This content is imported from Instagram. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Thoughts of African textiles often turn to bright, primary coloured cottons (the legacy of those Dutch wax prints), but authentic African textiles use natural dyes, one of the oldest being the ancient skill of indigo dying. In reality, midnight blue indigo is the most authentic colour of African textiles.

In need of some at-home inspiration? Sign up to our free weekly newsletter for skincare and self-care, the latest cultural hits to read and download, and the little luxuries that make staying in so much more satisfying.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

More Stories

A Melbourne Family’s Ever Changing ‘Light House’

The Dragonfly House Offers Best Views of Whitefish Lakes

A Floating House Entangled In Brush Box Trees